“Just the other day, they were talking about building another [immigrant prison] camp in Kelso, Arkansas. Whether you are a Republican or Democrat, a liberal or conservative, you know that’s a bad idea. I was out there the other day at Kelso. You could see the smokestack of the Rohwer camp from that site.” Richard Yada

The Ron Robinson Theater was filled with memory, emotion, and hope on Friday, July 13 at an unforgettable screening of Relocation, Arkansas: Aftermath of Incarceration.

The Ron Robinson Theater was filled with memory, emotion, and hope on Friday, July 13 at an unforgettable screening of Relocation, Arkansas: Aftermath of Incarceration.

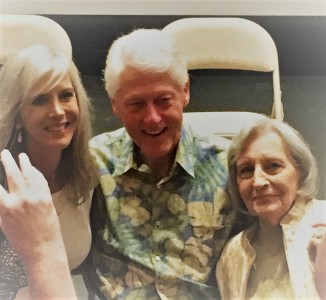

Sponsored by the CALS Butler Center, the Clinton School for Public Service, and the Arkansas Psychological Association, the screening was followed by a panel discussion. Survivors and descendants of Japanese American internment camps appeared in person for the discussion, led by director Vivienne Schiffer. President Bill Clinton was in attendance along with many leaders and well-known social justice figures from recent Arkansan history.

In the present day, the United States government faces an ethical crisis sparked by the incarceration of thousands of immigrants in prison camps. The audience heard in person from survivors of a similar imprisonment in American history that scarred psyches and families for decades. Testimony from survivors, descendants, and witnesses of past injustice brought home the power of historical lessons to change our present-day actions.

In the present day, the United States government faces an ethical crisis sparked by the incarceration of thousands of immigrants in prison camps. The audience heard in person from survivors of a similar imprisonment in American history that scarred psyches and families for decades. Testimony from survivors, descendants, and witnesses of past injustice brought home the power of historical lessons to change our present-day actions.

The film Relocation, Arkansas examines the aftermath of the internment of Japanese Americans in prison camps during World War II, when a wave of paranoia and prejudice caused the US government to imprison over 100,000 Japanese Americans nationwide. The families in the film were among the 8000 imprisoned in the Rohwer camp in Arkansas.

The incarceration had lifelong consequences not only for survivors, but for their children. The incarceration deprived these families of their jobs, their communities, and their homes, and left them to start over in strange towns. Even after release, the families still faced intense prejudice from many in the American population.

The incarceration had lifelong consequences not only for survivors, but for their children. The incarceration deprived these families of their jobs, their communities, and their homes, and left them to start over in strange towns. Even after release, the families still faced intense prejudice from many in the American population.

Paul Takemoto, cast member, grew up knowing that his mother Alice had survived the Rohwer incarceration. He had difficulty understanding or accepting the effects of that traumatic history on his own life and identity. At the age of 46, he met Rosalie Santine Gould, former mayor of McGehee, Arkansas, who had dedicated herself to supporting and hosting the survivors of the Arkansas internment camps.

“Sometimes you have these transformative single moments or events in life,” Mr. Takemoto said in the panel discussion. “For me, that event was hearing Ms. Rosalie talk about honoring the memory of events and people I had done my best to forget. There’s no greater gift you can give someone than their pride, and that’s what Ms. Rosalie did for us.”

Mr. Takemoto went on to relate how the artwork created by Japanese Americans incarcerated at Rohwer had been willed to Rosalie Gould, and was now on display at the Butler Center.

“Giving Ms. Rosalie their art was the most appropriate gift [survivors] could give,” Mr. Takemoto said. “Places like the Butler Center are now using that art as an expression of the humanness of the experience.”

Rev. Don Campbell, also on the panel, was in high school in Arkansas during the incarceration. He described the silence about the camps in the American media. “I read two newspapers a day and never heard of the camps until the summer of 1945 as a freshman at Yale.”

Rev. Campbell spoke movingly of the prejudice that dominated American culture then. “I think you need to know the mindset in this country at the time. I remember saying that we might one day make peace with the Germans, but that the Japanese were not human. I believed that because all the movies and propaganda depicted the Japanese as fierce and subhuman. You need to know how powerful propaganda can be, and how it can change people’s minds. And we need to remember that today.”

His words were followed by a loud burst of applause.

Director Vivienne ‘Lie’ Schiffer pointed out the courage of the Takemoto family, Richard Yada, and the others in the film who had exposed their personal lives with vulnerability in order to preserve the history of the camps and their consequences.

That bravery was apparent to Elizabeth Eckford, a member of the Little Rock Nine who appeared in the film and was present at the screening. Ms. Eckford knows personally of racial prejudice and its effects, and though she had seen the film before, she saw a new aspect at this screening. “What struck me this time,” she said, “was that the older generation of survivors was reluctant to talk about this experience. So it was very brave that Paul’s mother [Alice Takemoto], was willing to come forward and speak in the film.”

The clear injustice and cruelty faced by the families in the film left attendees deeply moved.

Attendee Mariah Hatta said, “That is the hardest film I’ve ever watched. I am Japanese American, and my father is still a Japanese national. He fought in the Japanese army during World War II.”

Attendee Mariah Hatta said, “That is the hardest film I’ve ever watched. I am Japanese American, and my father is still a Japanese national. He fought in the Japanese army during World War II.”

Another attendee, Liz, had a very personal connection to the film. “My father was an assistant administrator at the Jerome camp [the other Arkansas internment camp]. I was living there when I was 3 or 4, though I don’t remember it. But the film gave me a new perspective, because my father never talked about it.”

Skip Rutherford, Dean of the Clinton School of Public Service, said, “The timeliness of the film can’t be overstated. We never thought it could happen again, but here we are today facing many of the same issues.”

Butler Center Director David Stricklin said, “The CALS Butler Center work on the story of the camps in Arkansas is easily one of the most important things we’ve ever done. It is heartbreaking and inspiring at the same time.”

At the close of the panel discussion, Rev. Campbell emphasized both the need for action and hope for the present day. After telling the audience how certain young Arkansans had voiced fiercely racist sentiments and shunned the Rohwer survivors after their release, he explained that those persecutors later became the chief defenders of the Japanese Americans in school. He reminded the audience of one simple truth.

“Prejudice can be overcome.”

The artwork of the Rohwer camp survivors is now on display at the CALS Butler Center in Concordia Hall through December. The exhibition is a reflection on American identity entitled “A Matter of Mind and Heart.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.